The Institute Colloquium: Normal brain aging: Impact on circuits critical for memory

Date

Monday, September 9, 2013 16:30 - 17:30

Speaker

Carol A. Barnes (University of Arizona, Tucson)

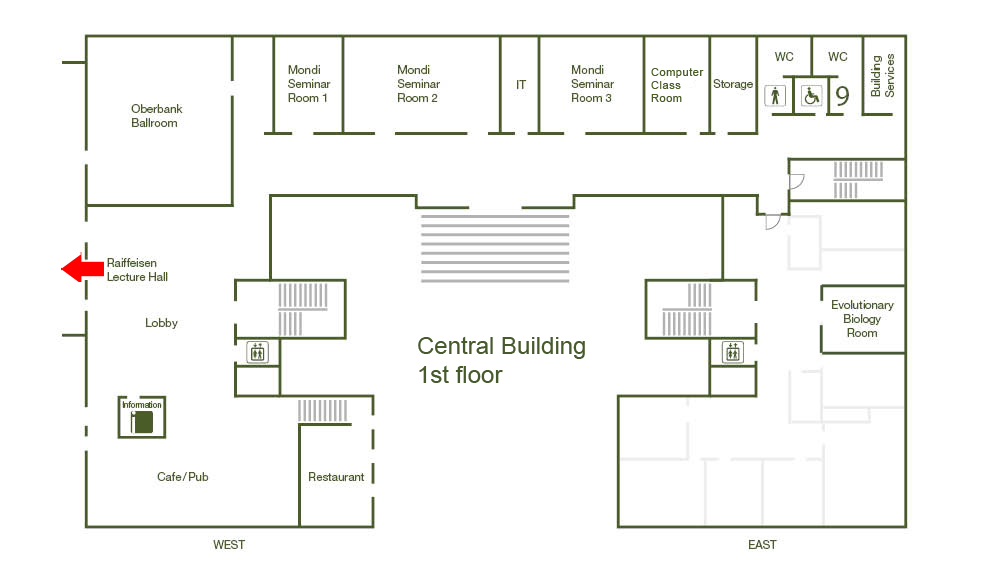

Location

Raiffeisen Lecture Hall, Central Building

Series

Colloquium

Tags

Institute Colloquium

Contact

Aging is associated with specific impairments of learning and memory, some of which are similar to those caused by damage to temporal or frontal lobe structures. For example, healthy older humans, monkeys and rats all show poorer spatial, recognition and working memory, than do their younger counterparts. Rats and monkeys do not develop age-related pathology such as Alzheimers and Parkinsons diseases, which makes them good models for assessing functional alterations associated with normal aging in humans. While many cellular properties of medial temporal lobe cells appear to be intact in aging animals, age-related impairments in synaptic function, plasticity and gene expression have been observed. Because information is represented by activity patterns across large populations of neurons, an understanding of the neural basis of cognitive changes in aging requires the examination of the dynamics of behaviorally-driven neural networks. Ensemble recording experiments are described that suggest fundamental changes in the storage and retrieval of information, as well as in high level perceptual processing in aging hippocampal and perirhinal cortical circuits. In addition, frontal cortical correlates of working memory are discussed. Together the evidence suggests that normative aging processes show both cell type and region specificity, and rather than uniform deterioration, the aging brain can show changes consistent with adaptive, compensatory processes.