Institute Colloquium : Genetics of antagonistic coevolution

Date

Monday, December 5, 2011 16:45 - 17:45

Speaker

Dieter Ebert (Basel University)

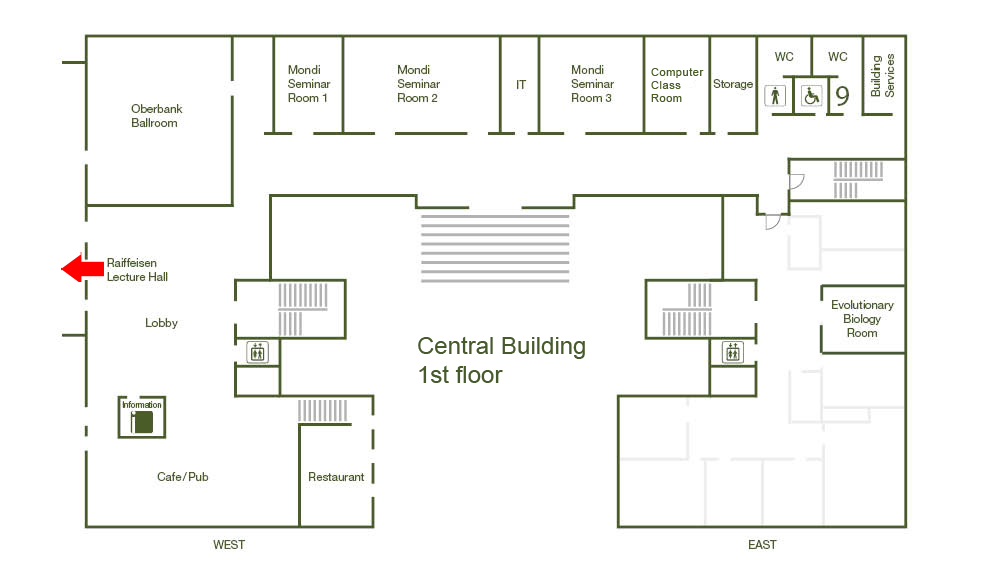

Location

Raiffeisen Lecture Hall, Central Building

Series

Colloquium

Tags

Institute Colloquium

Contact

Parasites are assumed to evolve to optimise their exploitation of hosts, while hosts evolve to minimize the damage done by the parasite. In coevolutionary models of this process high specificity in host parasite interactions are assumed. Furthermore, coevolutionary models make strict assumptions about the underlying genetics. Little is known about the genetic interactions between hosts and parasites. In the Daphnia system this can be conveniently addressed experimentally. Daphnia reproduce clonally in the laboratory and clones can be crossed to test for segregation of resistance loci. I present experimental data from our work on the genetics of resistance against two parasites of Daphnia magna: the bacterium Pasteuria ramosa and the microsporidium Hamiltosporidium tvaerminnensis. These parasites are virulent and common to D. magna population in Europe. In natural populations these parasites coevolve with their host. Using QTL mapping, de novo genome sequencing and classical breeding experiments, I present our insights into the nature of the genetics of antagonistic coevolution.