Institute Colloquium - Beyond Nature and Nurture: An Evolutionary Perspective on Bact

Date

Monday, November 14, 2011 16:45 - 17:45

Speaker

Martin Ackermann (ETH Zurich)

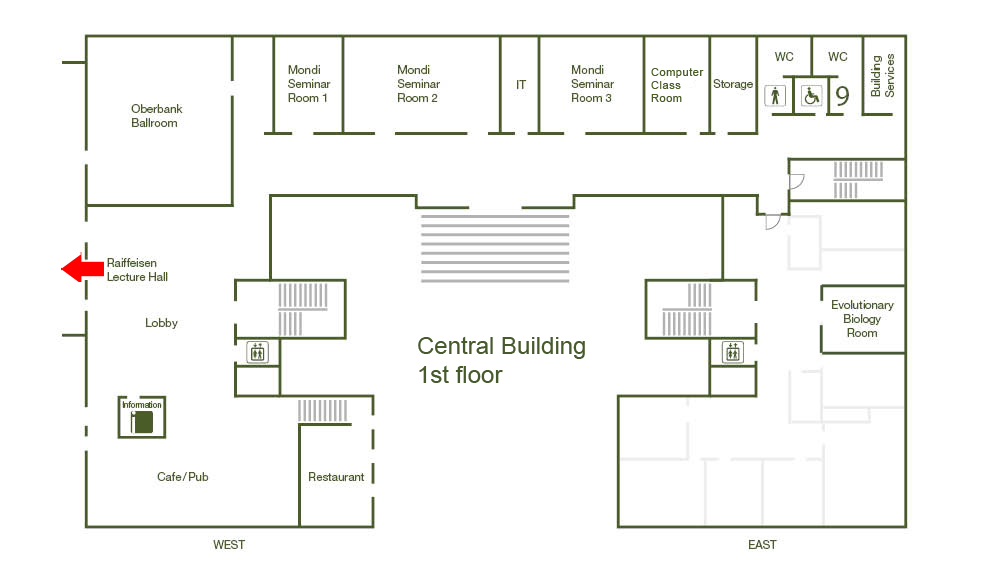

Location

Raiffeisen Lecture Hall, Central Building

Series

Colloquium

Tags

Institute Colloquium

Contact

According to the conventional view, the properties of an organism are a product of nature and nurture - of its genes and of the environment it lives in. One would thus expect that genetically identical individuals in a homogeneous environment would all be identical. Recent experiments with unicellular organisms have shown that this is not the case: different individuals in clonal families sometimes have markedly different properties, and express different genes. We are interested in the biological significance of this variation: is phenotypic heterogeneity sometimes beneficial, and does natural selection promote genotypes that produce different phenotypic variants in homogeneous environments? I will first present results that suggest that, for the majority of the genes in a bacterial genome, natural selection acts to reduce variation. Then, I will present a few exception to this rule, and discuss how phenotypic variation in clonal populations of bacteria can promote interactions between individuals, lead to the division of labor, and give clonal groups of bacteria new biological properties. Finally, I will briefly discuss molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial individuality, and show how seemingly stochastic phenotypic variation can have a deterministic molecular basis.